If the government continues to just solve pressure points on the road and in the railway system, that will eventually only create more cars and thus more pressure points. It is about time for us to start using our billions of euros for infrastructure in a different way. And then immediately take into account the effects of roads, such as road casualties and environmental damage. Because there are solutions that are more effective, cheaper and healthier than simply putting down more asphalt, cement and iron. More bicycles, more people in one vehicle and building in the areas around train stations are but a few examples.

What is the problem? Everything starts with the Multi-year programme for Infrastructure, Space and Transport (Meerjarenprogramma Infrastructuur, Ruimte en Transport or MIRT). This programme contains the projects of the central government and the regions for the creation of roads, railway lines and waterways, ranging from simple ring roads to gigantic projects. In the next few years, the total budget for approved projects will be 8.9 to 9.1 billion euros per year (including the management and maintenance of railways by ProRail and of roads by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management). That money will come out of the government’s fund for infrastructure projects called Infrastructuurfonds. The MIRT expires in 2032, meaning several future governments will be involved.

The regions (the four big urban areas in the Randstad conurbation, but also Arnhem/Nijmegen, Eindhoven, Groningen and Twente) barely have money of their own to adjust or create infrastructure. For projects of a decent size, the regions have to ask the central government for money, which then decides how the available budget will be divided. In practice, this means that large infrastructure projects of the central government get priority, with little money left for the regions.

1. Cash withdrawals for pressure points only

To put it bluntly, the MIRT is the ATM of the government: if you need any money for infrastructure projects, that’s the place to go. Problem 1 is that regions are only allowed to ‘withdraw cash’ if they can prove they are dealing with a pressure point. A pressure point is the weakest link in a piece of infrastructure. For example, places where different types of transport cross each other, places where the traffic flow stagnates or bottlenecks (where the roads changes from three lanes to two, or the railway from four tracks to two).

So how can a region know if the situation they are dealing with is a pressure point? This is decided every four years in the ‘National Market and Capacity Analysis’ (NMCA). That NMCA uses traffic models to determine where there will be pressure points in the coming years. Traffic models are computer programs which estimate how traffic is divided between destinations, types of transport, times of day and routes.

2. Car and public transport interchangeable?

It is common knowledge that if you use a model, the output is dependent on the input. Which in this case means 25 years of stagnated traffic and transport policy, with cars as star of the show. And that is problem 2 of our infrastructure policy: policy makers start from the assumption that cars, public transport and bicycles are non-communicating vessels. But thanks to innovations such as the e-bike or the OV-fiets bike sharing programme and more frequent public transport through systems such as ‘A Train Every Ten Minutes’ (for the intercity train between Amsterdam and Eindhoven), RandstadRail (express trams) and R-net and Q-link (express buses), we see that motorist abandon the traffic jams and start using alternatives. So it is possible to change travel behaviour after all, as long as the alternative is good enough.

3. Fictitious economic value

Traffic models mainly focus on travel time. Travel time lost due to pressure points. And travel time saved thanks to infrastructure projects which are supposed to solve those pressure points. The measure for travel time lost is the lost vehicle hour or LVH. One LVH can mean that one vehicle has a delay of one hour on a specific trajectory. Or that six cars are stuck in congestion for ten minutes. But what is not taken into account is how many people there are per vehicle. Models count vehicles, not people. In traffic models, one luxury taxi van or a minivan with 10 passengers is weighted in the same way as a car soloist: one individual car with just a driver. Which is problem number 3.

Every lost vehicle hour is attributed a fictitious economic value for the user. For example: an hour in the car for a business man or woman is worth over 26 euros. A commuter on the train is worth 11,50 euros. And for the moment, a commuter using a bicycle is worth 0 euros – according to the models, that is. As a region, you can rake in more money for new infrastructure if you send 1,000 people as car soloists through the Coentunnel bottleneck, than if you divide them over 100 luxury taxi vans or minivans. So on paper, the economic value of those 1,000 people is ten times as high when they each drive their own car as if they were divided over taxi vans. And if you would put them all on an e-bike, they would have no economical value at all.

My father was a cardiologist at the Kennemer Gasthuis hospital in the city of Haarlem. According to the government, his commute by car from our house in the neighbouring village of Aerdenhout to the hospital in Haarlem has economic value. But doing that same trajectory on an e-bike would have no value at all? And that while it would be quicker, cheaper, take up less space on the road, cause no pollution, not to mention keep him in good shape?

4. Flattening peaks through infrastructure?

4. Flattening peaks through infrastructure?

But when is a pressure point considered a pressure point? It turns out that the peak, meaning rush hour, is decisive. Most people only sporadically lose time in traffic congestion, according to the report ‘Blik op de file‘ (View on Traffic Congestion) of the Netherlands Institute for Transport Analysis (KiM). Motorists who hit a traffic jam at least once every week (15 percent) suffer an average delay of 43 minutes per week. Congestion that causes a delay of less than 10 minutes is not considered as a problem by most. And with such a matter-of-fact approach to pressure points, most of them aren’t really pressure points at all.

The definition of a pressure point for an intercity trainline is when, at the highest peak of rush hour, more than nine out of ten seats are taken on 10 percent of the days in the months of September, October and November. Although it is completely normal to stand for a while on the London tube or the Parisian RER (trains from the city centre to the suburbs), the Dutch railways already consider to be dealing with a pressure point when not everyone is able to sit down.

Problem 4: We build expensive infrastructure to flatten peaks, while it would be better to achieve this through cheaper measures such as rewarding people who travel outside rush hour or work from home (SpitsMijden or Avoiding Rush Hour), or spreading the start times of students and employees.

5. Costs for society not taken into consideration

The Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis and the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency conducted research into the biggest welfare effects of road projects. “With 81 percent, the vast majority of the monetised welfare effects are direct effects, mainly consisting of travel time saved,” is the conclusion of these two institutions in their report ‘Kansrijk Mobiliteitsbeleid‘ (Favourable Mobility Policy). “Travel time saved is therefore the most deciding factor in societal cost-benefit analyses with regard to capacity expansion.” External effects such as greenhouse emissions, particulate matter, noise pollution and traffic accidents together only account for 11 percent.

The Netherlands Institute for Transport Analysis (KiM) estimates that the societal costs of traffic congestion and delays on motorways are 3.3 to 4.3 billion euros per year. Approximately half of those costs are concrete: paid professional drivers who get stuck in congestion with their delivery van, bus, taxi or lorry. The societal costs of traffic accidents (nearly 700 deaths and 21,000 injuries per year, relatively many of which sustained by cyclists) and environmental damage caused by traffic are estimated at 18 to 24 billion euros by the KiM. So to achieve the biggest gain, we should not focus on reducing travel time lost (2 billion euros) but rather on reducing the damage to people and the environment. Problem 5: Societal costs are not taken into consideration during decisions on widening or building roads. Problem 6: the network effects on the, including pressure on parking availability, are not considered here either.

6. The city explodes

More can be said about the goal of reducing travel time lost. Travel time lost is measured from loop detector to loop detector in the asphalt (on motorways, not on underlying roads) or from train station to train station (using check-in and check-out data from the OV-chipkaart, the smart card and integrated ticketing system used for all public transport in the Netherlands). But those measurements on the road or railways are only half the story, because they only cover a part of the entire journey, forgetting the often time-consuming hunt for a parking spot (car) or pre- and after-journey transport (public transport). By just considering the central part of the journey, a large part of the problem remains unsolved. Especially if the aim is to reduce the total travel time – so the time from front door to front door.

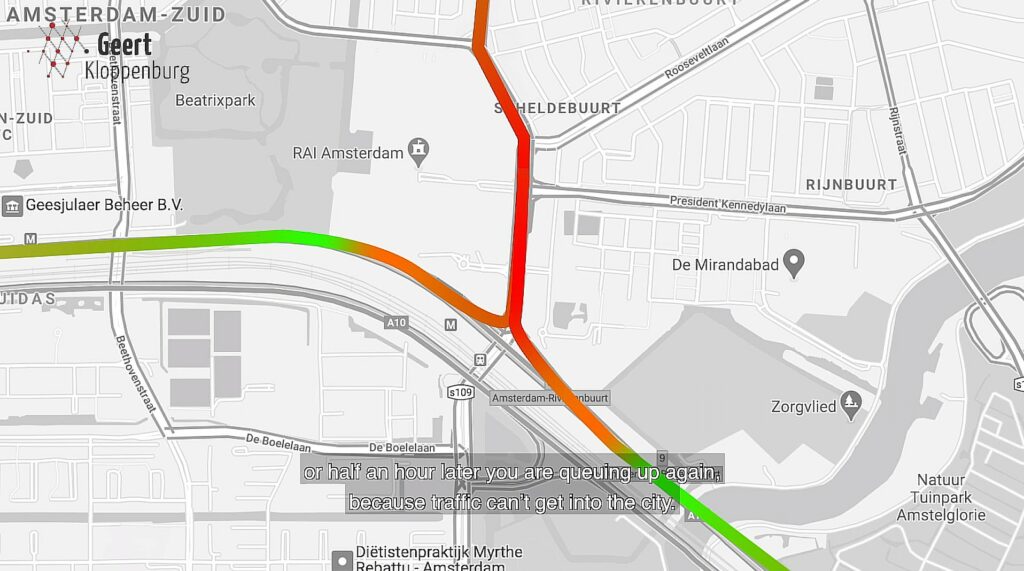

By way of illustration: cars on widened motorways may be able to drive smoothly again, but will they still get stuck on the access roads into the city. And there won’t be enough parking spaces left for all those extra cars. The result: an ‘exploding’ city with too many parked cars, too little air, too little space, too much traffic, too much nuisance. Widening motorways is no longer an adequate solution for achieving a quick or reliable journey.

The same is true for train travel: there is little point in spending millions to build additional tracks (for more trains) if there is no space to park your bike at the departure station. Or if the last mile from the arrival station to your final destination takes a disproportionate amount of time. It is more cost-effective to speed up those first and last parts of the journey (by creating bicycle parking, fast cycling routes, shared bike systems) than building expensive infrastructure for the central part. But that is a type of travel time saved which the NMCA doesn’t know, which is problem number 6. As a society we concentrate too much on motorways and railway tracks, failing to see solutions that are both practical and simple.

7. Solutions of a time gone by

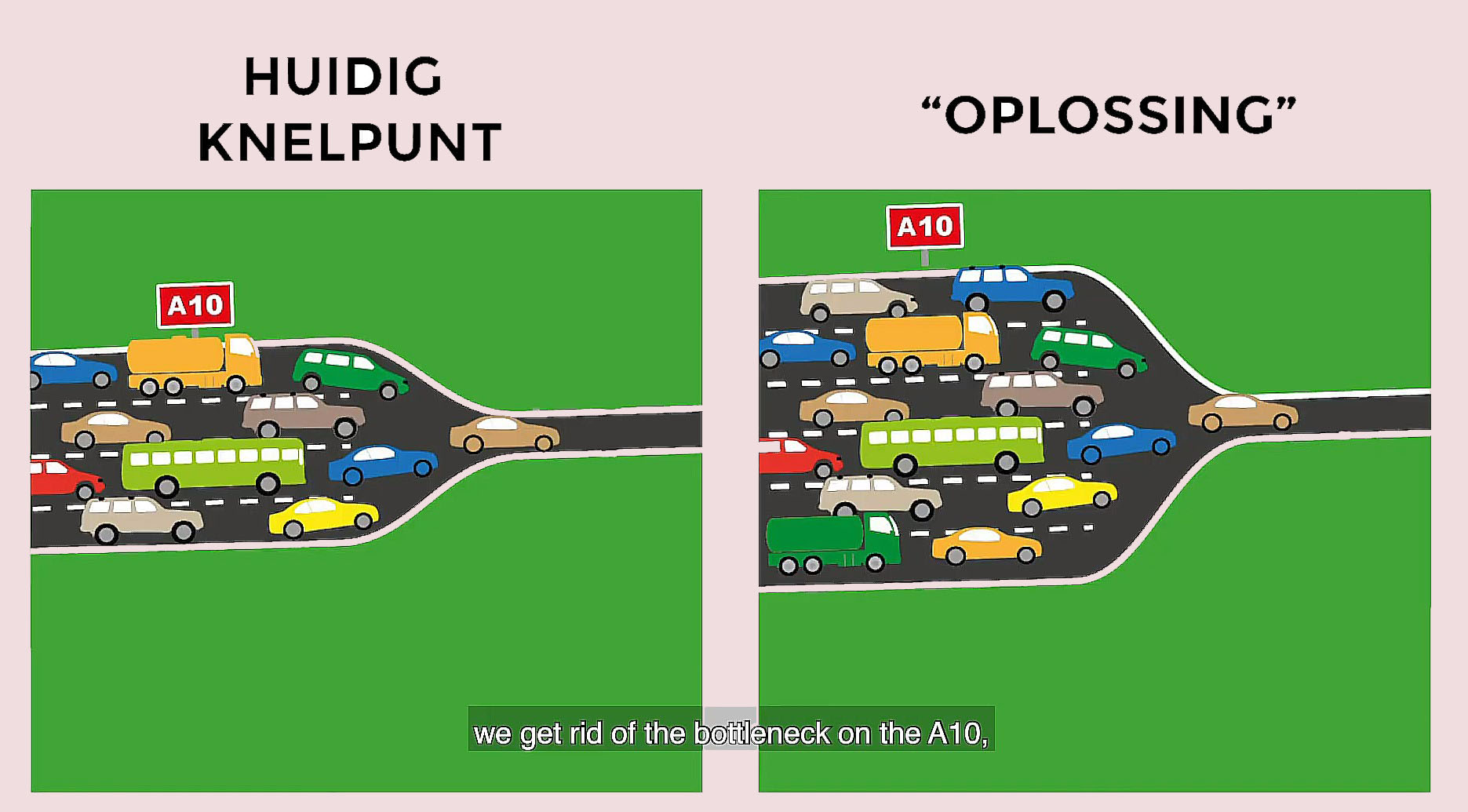

If a region, after much fuss and lobbying, manages to get its pressure point acknowledged, a whole MIRT circus starts up: pre-exploration, formal exploration, research, more in-depth research, plan development. It can take up to ten years before a pressure point leads to a project. And that is before starting the construction. Many infrastructure projects being executed today are the solution to problems of twenty years ago. At that point, nobody dares questioning anymore whether the project that was drawn up then is still the solution of today – problem number 7. The assumed economic return of projects is very rarely achieved. Additional car lanes immediately fill up again with new traffic. In part because there is no targeted control by the government. Traffic control at ProRail and Schiphol Airport or network administrator TenneT would never let such a thing happen with new railway tracks, runways or electricity cables.

8. No room for new solutions

In the MIRT, there is no room for new forms of transport or smart solutions, which is problem number 8. Because what would happen if, for instance, we would dedicate one motorway lane to collective transport (travelling together in one vehicle) only? Examples of this kind of transport are Bus Rapid Transit (frequent motorway buses), Flixbus, minivans, Über or even private cars with a minimum of four passengers. Make the providers of these services pay a fixed amount to use that dedicated lane.

Change the lay-out of access roads: less space for car soloists, a dedicated lane for collective transport. All it would take is a few pots of white paint and some traffic signs to change access roads like the Coolsingel in Rotterdam, the Croeselaan in Utrecht and the Wibautstraat in Amsterdam. Convert moderately occupied car parks to bicycle parks that will be used to the fullest. There are plenty of alternatives. Implementing a mix of measures works better than creating more asphalt and space for cars, especially in urban areas. But such measures are often too small for the MIRT and too expensive for the regions. For example, the Groningen region may have the most effective measures planned for bicycles, public transport, Park+Ride and SpitsMijden – if they don’t have a pressure point, they won’t get a penny.

9. Space does not count

Regions are unable to submit a request for 0 euros, asking not for expensive infrastructure but for strict direction from the government to improve the traffic situation. And it is very difficult for regions to get money from the MIRT for increased residential density around train stations. More offices, amenities and housing around train stations result in less new traffic, which means a worse score in the NMCA and thus no money. While increased density is a structural solution. Before, the MIRT was called the MIT: Multi-year programme for Infrastructure and Transport. The R of Ruimte (Space) was added later, but does not have any weight in the MIRT.

Then what?

Then what?

Conclusion: based on wrong assumptions, the MIRT currently uses too much money to solve old pressure points (mainly peak load) with extensive road and railway infrastructure, it does not result in more sensible travel behaviour and it displaces problems to the cities.

There are currently six million cars in the Randstad conurbation. Until 2040, a million more houses have to be built in the Randstad, which will result in an additional million cars. So that six million turns into seven million cars. Just think about what that means. For parking spots. For the length of traffic jams. For travel times. For the emission of CO2, particulate matter and nitrogen. Or, if those million additional cars were to be electric, for the energy grid. For the number of (fatal) traffic accidents. The point is clear: if there will be a million cars more in the already congested Randstad conurbation, not a single policy objective with regard to mobility, climate and road safety will be met.

So we shouldn’t invest even more millions of euros in our infrastructure. Also because, besides road and railway projects, there are many other, very expensive projects coming up: the energy transitions, climate resiliency, urbanisation, house construction… Immense societal projects which also require billions of euros.

So if investing in infrastructure is not the solution, then what is? The assessment criteria for money from the MIRT are in dire need of thorough revision. Scientists have been saying that for years. Currently, all parties are keeping each other hostage. Civil servants only sound the alarm behind closed doors. Administrators change roles too often to be able to thoroughly evaluate the infrastructure policy. And consultants are not allowed to look for other criteria, solutions or forms of transport. We could use those billions of euros for infrastructure in a more effective way. The problem is not a lack of money, but a lack of creativity. There isn’t a shortage of infrastructure, but a shortage of sensible use of it.

So go on and start giving economic value to all forms of transport that currently score zero euros per hour. And add a weighting for environmental damage (for example by adding an amount per ton of CO2 or nitrogen emitted) and traffic accidents. You will see that bicycles, collective transport and strict direction will then come up as solutions. We will be able to cancel half of the big infrastructure projects until 2032, which will leave us with billions to spare. And then we can have a good think about the kind of country and cities we want to live in and the kind of infrastructure and other measures that correspond with that. In short: let’s move from nonsensical infrastructure for vehicles to smart mobility for people.