‘I keep thinking: am I going mad?’

What is it like cycling to school at 8.15 in the morning, between rows and rows of cars and lorries? Geert Kloppenburg shows the traffic reality in videos containing countless close calls. “Who would design this?”

When Geert Kloppenburg roams the streets, the things he sees are very different to what local authorities describe in their policy papers. He gets on a bike, steps into a car, sits in the cabin of a lorry driver, joins a delivery driver during his rounds and he observes, observes and observes some more. And he films. Inspired by the findings of data guru Marleen Stikker, he demonstrates that the wrong kind of data is being used. “I keep thinking: am I going mad? I have been standing here in the rain for a while now and I honestly see something completely different to what is described in that policy paper. I know they talk about an average number, but that says nothing about the real danger of what is happening here.”

You mean: on average, only 0.1 pupil a year has a fatal accident here, but I see so many dangerous things happening here.

“Yes, this is a traffic situation both young and older people have to deal with. And that situation happens 250 days a year, every morning; that is what my new film is about.”

What Kloppenburg wants to show is that there is something fundamentally wrong. Cyclists, pedestrians, cars, delivery vans and lorries encounter each other too often. “That lorry driver would also rather be somewhere else. He obviously doesn’t set out to kill three elderly people. But if you consider the amount of traffic here, on a structural basis, then you can’t help but think: who would design this? At an intersection like that, the essence is not about who has the right of way.”

Always about behaviour

Kloppenburg feels for lorry drivers: “A lorry driver will say: ‘I can’t see a thing. That mirror will help me to see from here to there, but that’s it.’ And then when an accident has happened, they will say: ‘we did visit the school and explain about the blind angle.’ So that is what we do in the Netherlands: we send a police man and a lorry driver into the classrooms to explain that you should be careful when a lorry is turning. It is always about behaviour. Don’t use your mobile phone, don’t drink, use your lights. What we don’t do is analyse the situation, make a calculation of probability. Because this doesn’t just involve one intersection, it involves fifty intersections. That youngster, or that elderly person, will encounter that delivery van or lorry four times more. And that also becomes clear in the videos I made.”

Delivery vans

Delivery vans

During his research, Kloppenburg realises that the situations he is pointing out cannot be deduced from the data of the local authorities. Take the delivery vans for example: the reality of those in the residential areas is not included in the policy papers. On several occasions, Kloppenburg joined drivers on their rounds. “That is when you realise what a nightmare it is and what happens on the phones of those drivers: ‘Parcel delivery street X, 9 a.m.; parcel delivery 9.10 a.m.; parcel delivery 9.20 a.m.’. Just think about how such a driver functions in the system [LH1] and about how many delivery vans are on the streets at any given time. Nobody realises it, but structurally there are fifty of those vans in a residential area at the same time, because loads are not combined. If you order on the internet, there are different delivery companies. You only see how many vans there really are when using a drone to look at the area from above. And what do the policy reports say? Delivery vans don’t drive many kilometres. That is not what you should be measuring, kilometres are not the right parameter. Those reports say that there are much less delivery vans than cars. But what counts is the number of movements. They constantly drive through the residential areas, every front door has become a shop and they do double rounds, meaning that at 7.15 p.m., when a child comes back from sports practice, they’re back in the area. That is not a single incident, that happens every day. Why do I not see that data in the policy papers?” The structural chance that someone gets hit in traffic has increased, says Kloppenburg: “Nobody calculates that chance. It is not about black spots (places where many accidents happen, Ed.), it is about the structural chance of someone getting hit. That chance has increased significantly.”

Why is that?

In the past 25 years, ordering things to be delivered has become extremely popular, so there are a lot more movements of delivery vans in residential areas today. Add to that the fact that the number of cars parked in those areas has doubled. There are more two-earner households, with two people travelling for work. Elderly people also travel more these days. And cars have become much wider and higher. And you can say ‘they have only increased by ten centimetres’, but in a city, ten centimetres is a lot. Just have a look around and you will realise how little visibility there is in those narrow streets full of parked cars.”

Black spots

Black spots

In Kloppenburg’s opinion, traffic safety policy focuses too much on black spots. He wants to address the iceberg: the high number of accidents that are not included in the registers of the police and hospitals. “All those broken ankles, the falls due to a car door opening. That is the real elephant in the room. That massive category of accidents that are not classed as deadly or involving severe injuries. Insurers are aware of these, because they are the ones who receive the claims for car damage in these types of accidents. It is known that in the municipality of The Hague, there are approximately 350 of these accidents with cyclists and pedestrians every day. That is much more than we ever thought, it basically happens every day. But we don’t see that in the traffic safety statistics.”

Unacceptably high risks

“You could say that it comes with the territory, but I showed these videos to really good safety professionals. And the reaction of such a safety professional at Shell was: ‘if we would structurally let situations like the ones you describe happen here, the refinery would could have to close tomorrow. Our licence would be revoked.’ And a safety professional at the Dutch association for construction and infrastructure Bouwend Nederland said the same: that wouldn’t be allowed on a construction site, where everything evolves around eliminating risks.”

No more travel?

“People’s reaction is often: ‘so I can’t travel anymore?’. But that is not what I am saying. What I am saying is that currently too little is being done to eliminate the movements of time and place. To illustrate it, I will point to that sign saying ‘lorries allowed from 8 a.m.’. That really infuriates me. And this is what is happening in the whole country. Supply deliveries are allowed from 8 a.m., even when the delivery location is next to a school. Then you can talk all you want about changing behaviour and add another mirror, but if you tell them to come at 8 a.m. then that is what they will do. The design is not neutral, the problem is caused by the design. Behaviour is not the issue here. No, this is designed unsafety.”

TEXT: KARIN BROER – ILLUSTRATIONS: SIMON CORDES – PHOTOGRAPHY : PAUL VREEK/UNITEDPHOTOS AND DIGIDAAN

“The flexibility, the flagging down, the absence of a timetable. That also more or less summed up what I knew about it. It made me think of old-fashioned taxis, but at the same time it’s a form of public transport, which was a trigger for me. Is it really a form of public transport? Who drives these vans? And who decides their itinerary? Who decides how much you pay to use it? Is it possible to implement this in other European cities?”

“The flexibility, the flagging down, the absence of a timetable. That also more or less summed up what I knew about it. It made me think of old-fashioned taxis, but at the same time it’s a form of public transport, which was a trigger for me. Is it really a form of public transport? Who drives these vans? And who decides their itinerary? Who decides how much you pay to use it? Is it possible to implement this in other European cities?” After all that preliminary research, it is time to visit Istanbul in October. As always, Kloppenburg arrives in town three days before his first interview. Now, where to find those dolmuş vans and minibuses? He sees blues vans, yellow vans, all sorts of vans, but what is what? Kloppenburg: “In the end, I just got on one, thinking ‘I’ll soon find out’. And it went in the complete opposite direction of what I had intended. I didn’t understand how much I had to pay, I didn’t understand which lines there were, where the starting points were – I quite simply didn’t understand one iota.” He did not have a map of the network. Eventually, he figured out that the lines could be found on Google maps.

After all that preliminary research, it is time to visit Istanbul in October. As always, Kloppenburg arrives in town three days before his first interview. Now, where to find those dolmuş vans and minibuses? He sees blues vans, yellow vans, all sorts of vans, but what is what? Kloppenburg: “In the end, I just got on one, thinking ‘I’ll soon find out’. And it went in the complete opposite direction of what I had intended. I didn’t understand how much I had to pay, I didn’t understand which lines there were, where the starting points were – I quite simply didn’t understand one iota.” He did not have a map of the network. Eventually, he figured out that the lines could be found on Google maps.

One out of three flight itineraries within Europe can also be done by train in less than six hours. Still millions of Europeans prefer to fly. This is mainly because the fantastic European public transport systems are all just a few stops short of being interconnected. And because it is incredibly complicated to plan, book and pay for an international train journey. In the past year, I investigated the issues people encounter when wanting to travel through Europe by train – and found out how we can simplify things.

One out of three flight itineraries within Europe can also be done by train in less than six hours. Still millions of Europeans prefer to fly. This is mainly because the fantastic European public transport systems are all just a few stops short of being interconnected. And because it is incredibly complicated to plan, book and pay for an international train journey. In the past year, I investigated the issues people encounter when wanting to travel through Europe by train – and found out how we can simplify things. The three major issues of international train travel

The three major issues of international train travel

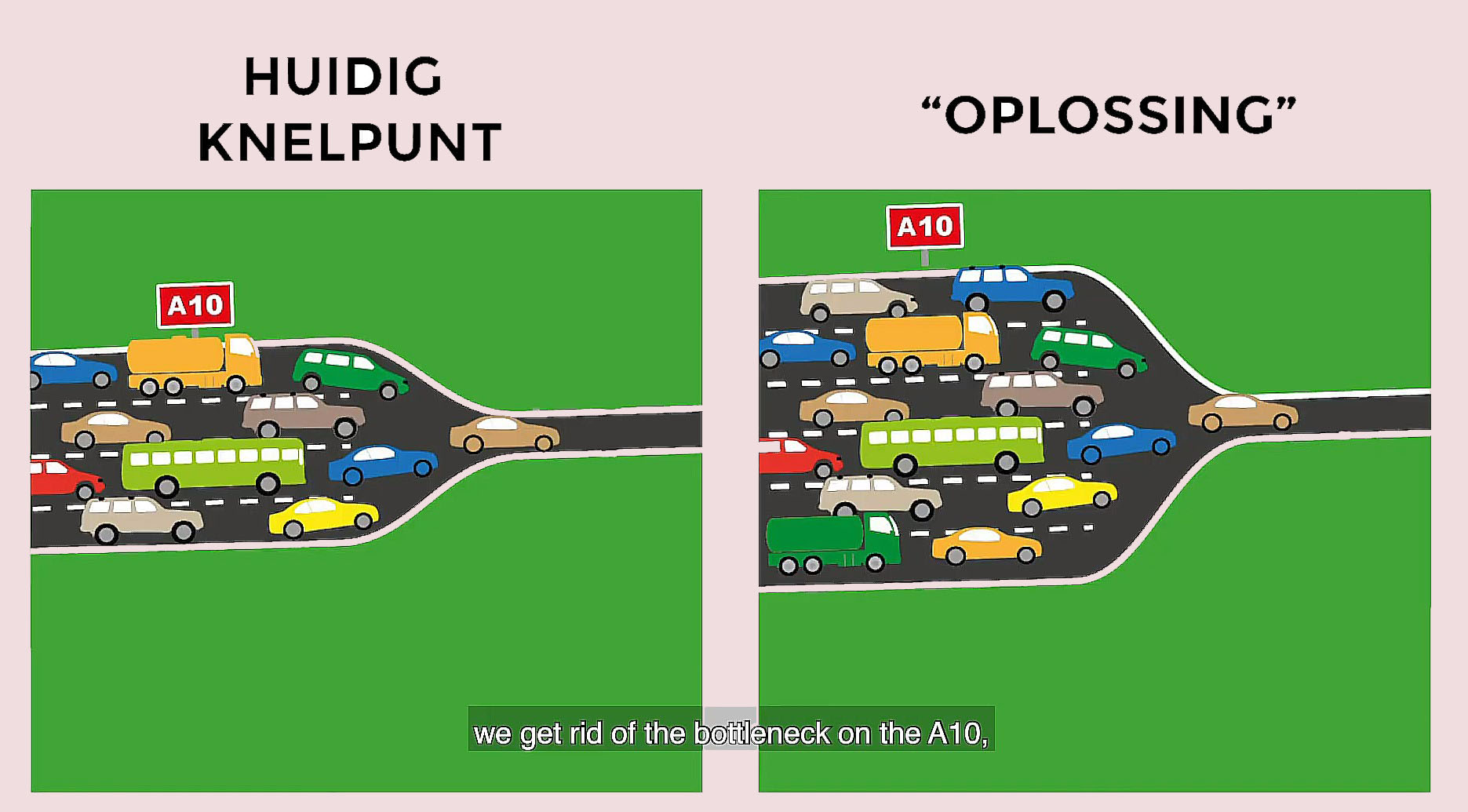

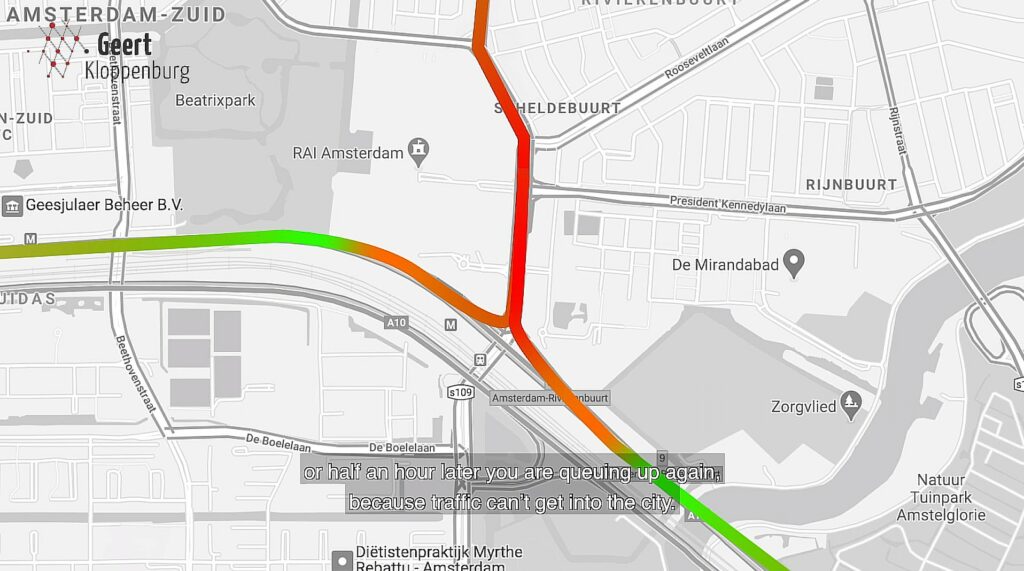

4. Flattening peaks through infrastructure?

4. Flattening peaks through infrastructure? Then what?

Then what?